Fashion cannot exist without change, but some changes reach beyond the season. When it was announced last year that Chanel was without a creative director, people across the industry looked to the house in nervous expectation. For nearly 40 years, Chanel had articulated the vision of one man: Karl Lagerfeld. After he died, in 2019, his longtime deputy Virginie Viard had carried on his style. Viard’s departure last year opened one of the highest seats in fashion, but also raised the possibility that Chanel’s taste could take a startling turn. Matthieu Blazy, a comparatively young designer who had distinguished himself doing surprising things with leather at Bottega Veneta, was not considered an obvious choice, and when he was announced as artistic director last December, he had the task not just of working his way out from a very long shadow but of showing where, as a designer of largely unknown capacities, he might go. The future course of the house would come down to his October debut.

When the night of that first show arrives, the vaulted backstage of the Grand Palais, a Beaux Arts wonder on the banks of the Seine, shivers with preparation. The floor, covered in light grey felt, is taped off with a runway order. Models rush and loiter in robes and hair clips. Forty minutes before the showtime of 8 p.m., Blazy appears, looking tense and pale. “I’m a bit all over the place, to be honest—I’m going to have a cigarette,” he says, and rushes off again.

Blazy arrived at Bottega after a nearly 20-year career as a deputy at work in the shadows, a secret weapon who had become an open secret. At Raf Simons, where he began out of school, he was known for introducing complexity into patternmaking; at Maison Margiela, he designed the crystal-studded masks that became one of the house’s emblems. His work at Bottega was characterised by a sophisticated understanding of craft and its capacity to hold apparently contradictory ideas in surprisingly human wholes. “It’s strength meets softness, structure meets fluidity,” says Ayo Edebiri, who is attending the show as a Chanel ambassador. “But also, he sees every type of woman. I feel like myself in a really gorgeous dress, but it could be sexy or demure.” Nicole Kidman, a longtime affiliate of Chanel, says, “From the moment I met Matthieu, I was struck by the way he approaches everything with his heart first.”

Four screens to one side of the room offer a window to the world outside: the interior of the hall, two views of red-carpet arrivals, and drone surveillance of the teeming crowds behind gates on the sidewalk outside. Everyone is searching for Blazy. The models are taking their spots in the lineup; audiovisual workers murmur into their earpieces. When the designer finally appears, he makes a brisk tour, smiles widely at his colleagues, then retreats to his own nerves. He’s worried about nothing in particular, and about everything, he says. “My mom describes it as the stress when you drop your kids off for school on the first day—you know it’s going to be fine, but still,” he says, wrapping his arms tightly around himself and looking at the models waiting to be counted off. He glances from the screens to the models, then adds, with an air of cautious contentment, “It feels like the big leap.”

Some weeks earlier, one warm Wednesday evening in July, I met Blazy on the steps of the Église Saint-Germain-des-Prés, the oldest church in Paris and, as its name suggests, a monument once surrounded by meadows. Today it’s a testament to the power of perdurance—the way that a peripheral feature standing long enough cannot just blend into the landscape but become its defining attribute, the heart of its allure.

For Blazy, it is also home. “I live not far from here,” he says, rising from his crouch on the church steps to greet me. “And my father had a gallery nearby, so growing up I was here constantly.” He is neither tall nor short, and is wearing his signature white T-shirt—no logo—with a natural-coloured sweater around his shoulders and relaxed, faded blue jeans with exquisite black crinkled lambskin loafers of his own design. At Bottega, where I met him a few years ago, he was known for turning high refinement toward a youthful celebration of ecstatic daily life. I watched him at one of his first engagements, a banquet of grandees in Italy, as he stood to give a friendly, bashful address, his role seeming like a crown still deliriously large on his 37-year-old head.

HOLDING PATTERN

Models Abeny Nhial and Awar Odhiang. Chanel throughout. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech. Photographed by Rafael Pavarotti. Vogue, December 2025.

Only three years have passed since then, but at 41, with the Chanel diadem upon him, Blazy carries a more assured and weathered air. The light brown hair, worn in an all-purpose crop, bears flecks of gray. The face, more squarely adult now, has a certitude in the jaw and an impatience in the eyes. But most remains unchanged about a designer once described to me as having the air of an eternal student: attentive, self-effacing, and eager to join in.

“There’s a kind of creative who constantly needs to lead, and then there’s a kind of creative who’s willing to step back, listen, and offer the services of their brain, their Rolodex, their aesthetic intention,” the artist Theaster Gates, who collaborated with Blazy at Bottega on leather-clad ceramic pieces for the Mori Art Museum, tells me. In a pressured industry, Blazy holds a reputation for translating artistic freedom into surprising market success while also managing to be, as Simons put it, “one of the loveliest people I’ve ever met in my life.”

Blazy has led me down the rue de l’Abbaye to what appears, at first, the least prepossessing bistro in the area. At an hour when the 6th arrondissement is buzzing with workers loosed from their offices and out for a glass, it’s a dead space covered inside and out in boxy green trellis, with windowsills carpeted in what looks like AstroTurf. “This is the kind of café that is not very popular with tourists,” Blazy observes cheerfully, nodding to its open tables. Then he adds, “It’s also not too popular with the French.”

To him, though, the bistro is perfect, rich in singular details that people of more heedless taste might have scrubbed away.

“I love the sign La Santé par L’Alimentation”—health through food—he marvels, pointing to italic lettering over the door: It reflects a particular era and idiom. He likes the wicker chairs and, yes, the AstroTurf. Through Blazy’s gaze, what looks outlandish is often revealed to be truer to itself than, for instance, the nearby tourist restaurants with candles burning down over beef bourguignon and accordions huffing in the corner. He takes a seat outdoors at a small table bearing a small vase of lavender, and orders what the French call rosé piscine—pink wine with ice sloshed in.

Zeroing in on details—specific to time and place and shaped by the necessities of everyday living—is central to Blazy’s idea of integrity and rigor. He will often say he has made a collection before a single garment is designed. What he means is that he and his research chief, Marie-Valentine Girbal, have—arduously, carefully—collected dozens of mood board images and swatches in binders, labelled as specific looks. From there, the binders go on to his design deputies who, with free rein, mock up pieces inspired by what they see; then Blazy and the deputies spend weeks working over these propositions, nixing some, refining details on others. But that’s the workday. The binders are Blazy’s vision of what’s next.

The first time Blazy was asked what his vision of Chanel was, the answer came to him swiftly—he blurted it out—and worried that it sounded foolish: “I said, ‘Chanel is modern.’”

What that means, though, is interpretation. Where the Lagerfeld style at Chanel was effulgent and relentlessly chic—a sparkling Champagne flute transmuted into fashion—Blazy was a conceptualist with a taste for marked geometry and earthy color: His collections at Bottega centered on rich browns, purples au beurre monté, and bright, unusual hues of green. And where Lagerfeld was a monarch butterfly of excess—moving with an entourage; augmenting his Paris mansion with a separate, nearby Paris mansion for eating in; and filling these premises with books and the spoils of what André Leon Talley called his “Versailles complex”—Blazy’s taste is distinctly lower-key. He travels alone, often on foot, and prefers beer to Champagne. On coming to Paris to take the most rarefied job in fashion, he had his best furniture delivered to his office and, ever the student, arranged to move into a flat that he could share with his twin sister.

“He’s a remarkable choice for Chanel, in terms of his own personality and the way that comes across in his clothes,” Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge of The Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute, who two years ago organized a tremendous retrospective of Lagerfeld’s work, told me. “He has a very democratic and egalitarian approach to design, which I think will be enormously helpful to Chanel. I always felt with Karl that there was a sense of the sublime in his work achieved through luxury. Matthieu’s sublime is a bit quieter. He’s very much engaged with an aesthetics of the everyday.”

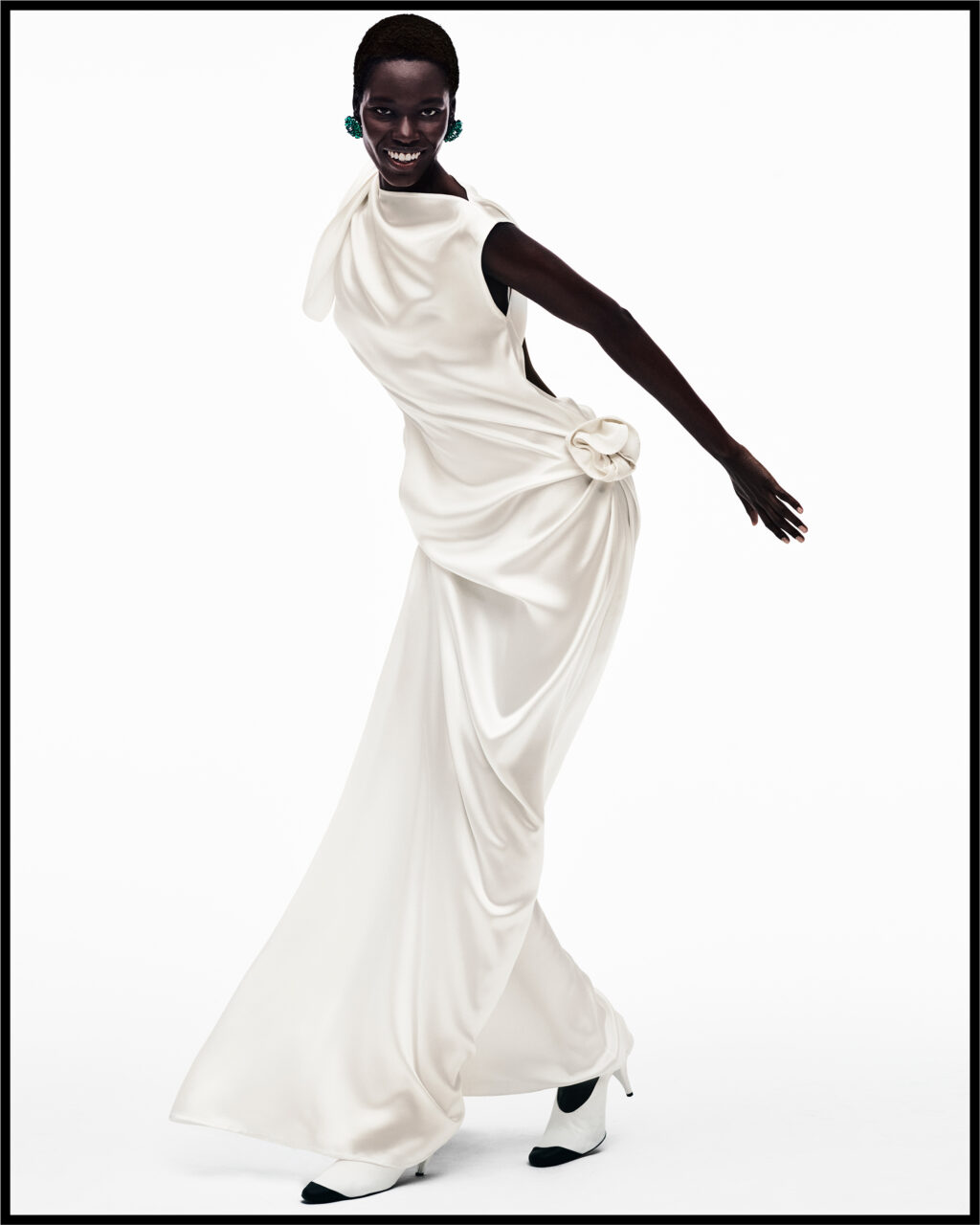

MAKING THE CUT

Model Aditsa Berzenia in a look that set the tone for Blazy’s debut Chanel show. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech. Photographed by Rafael Pavarotti. Vogue, December 2025.

A light summer rain has begun to fall. Blazy glances upward at it quizzically and asks whether I want to move. But we like the drizzle, so he lights a Marlboro Gold and orders another piscine and goes with the weather. For the first several weeks of his courtship by Chanel, he says, he had no idea what was going on. One day at Bottega, on his way out of a meeting, he received a call from a recruiter. “I figured out very quickly that if he was calling me now, he really had something,” Blazy says. He peppered him with questions. Was it this? That? “We all knew there was this game of musical chairs,” he explains. “At some point I was like, Fuck, maybe it’s Chanel—but I didn’t even dare ask.”

Blazy was on a train to Venice when he received a call telling him which job he was up for. Almost before he could recover, meetings were being scheduled.

“This was July,” he says. “It was a superhot day when I arrived in Paris. I was completely overdressed, but it was that situation where you don’t want to take off your sweater because it would fuck up your styling.” Sweltering for his art, he arrived for four hours of meetings with the house’s leadership—startled, he says, by how warm, tight-knit, and easygoing they seemed. “When I left the meeting, I thought”—he gives a sigh of resignation, like someone who has just fallen in love—“Fuck, I could be really happy with these people.”

He flew to London to talk with Leena Nair, the brand’s CEO. He traveled to Normandy to visit Alain Wertheimer, the company chair. “We almost didn’t speak about Chanel,” Blazy says. “He told me, ‘If you’re in front of me, it means you’re supposed to be a good designer, so let’s not talk about work.’” They conferred instead about childhood, about family, about their shared interests in art. During the last five minutes of the interview, Wertheimer circled back to fashion, and that was when Blazy made his remark about modernity.

“He asked me, ‘Do you think Chanel is modern now?’ I said, ‘I think the pillars are still modern, but we can push it.’” On which Wertheimer smiled. In the car home, the driver blasted French rap with the windows down, and Blazy allowed himself a moment of contentment. “That’s when I thought, Maybe this could work,” he says.

Bruno Pavlovsky, the president of fashion at Chanel, tells me that he and his colleagues had a very clear idea of the designer they were looking for: a genius who could inhabit the brand. “With some designers, it’s about their vision, even as they go from one brand to another,” he says. “What we have learned to like at Chanel is a chameleon”: someone who would use their imaginative brilliance to revivify the house on its own terms. “Matthieu has a vision—we love him as Matthieu—but he puts everything behind the brand.”

Outside the green bistro, the rain is getting heavy. Blazy proposes that we walk to one of his favorite restaurants, a couple of blocks away. As we rush down the rue Cardinale and the rue de Suisses, he recalls the moment when his appointment was announced and the secret of his Chanel role became global news.

“I freaked out,” he says. “I was scared. I was in a fish restaurant in Milan, and the waiter came over to me holding up Instagram saying, ‘You’re on my feed!’ He wasn’t somebody who even knew I worked in fashion.” Feeling a sudden, panicked urge to flee from the knowing eyes he felt would now meet him in every doorway, he packed a bag and ran from town, hiding in the south of Italy for 10 days.

Now waiters in white striped shirts and gray ties greet him. Blazy explains that he recently stumbled upon this place, which, although it looks at first glance like a Saint-Germain tourist-trap brasserie, turns out to be one of the oldest extant restaurants in Paris, with the original Art Nouveau woodwork. He orders beef chateaubriand, rare, with béarnaise and French beans and a pint of beer; when the plates arrive, he looks at the food, then me, then the food, and makes a gesture of amazement.

Blazy says he is pleased with the summer’s work; his studio has begun to come up with good ideas. “Everyone tells me, ‘I’m so excited about your show.’ But I’m so excited too—I don’t know quite what it is exactly yet. There is an idea of the whole that won’t change,” he says and gives an uncertain shrug. “Now what needs to happen is the magic.”

WINDOW DRESSING

While Blazy—photographed here atop Chanel headquarters in Paris—is very happy with his debut, he’s adamant that it’s all a work in progress. “I need to test ideas,” he says. “I want to make mistakes. It doesn’t have to be perfect—it’s a proposal.” Sittings Editor: Jack Borkett. Photographed by Annie Leibovitz. Vogue, December 2025.

tart with a coat. A men’s sport coat—British, say—in tweed: the everyday archetype of refined masculinity. Put it on a woman. Take a pair of shears to the bottom; cut it at the hip. Close the lapels. Add a button or two. “Suddenly you have the archetype of a Chanel jacket—from a man’s,” Blazy tells me. He knows this because he undertook exactly that operation with his team on his first day in the Chanel studio. It was an exercise in stripping away a century of thickly layered development at the house, returning to the original shock of the new.

“The way Karl looked at Chanel is a very specific point of view on what Chanel is,” Blazy explains. “When you go back to the early years of Gabrielle Chanel, a lot of things happened that haven’t been told yet, even though they resulted in codes.” On being shown Lagerfeld’s fitting room at the Paris atelier, Blazy knew he couldn’t work there—“too charged with legacy and pressure”—and set up a studio on the opposite side of the building in a simple, modern, light-filled blank canvas of a room. Rather than continuing on the roadways where Lagerfeld and Viard parked the brand, he would return to the creative path of Gabrielle “Coco” Chanel and take a different turn. The men’s-jacket exercise announced that change. But it also hinted at Blazy’s theory of the big bang that had created Chanel.

On beginning the new job, Blazy had spent time in the house archives while doing his own reconnaissance and research. On a hunch he spoke with Jean-Claude and Anne-Marie Colban, the brother and sister who direct the storied men’s shirting tailor Charvet. “They knew things I didn’t know—that, for example, Coco would buy gifts for her boyfriend in that store,” he says.

The boyfriend was Arthur “Boy” Capel, an English polo player whom Chanel was madly in love with from 1909 until his death a decade later—the years when her style, career, and mystique seemed to materialize from the mist. Blazy imagined Coco putting in Charvet orders, studying the fitted male shoulder and plackets of the shirts. And he knew that Capel, an upper-class English sportsman, wore a lot of tweed.

In the early 1910s, Coco attended a fancy-dress party in men’s clothes. Unlike most of the other guests, she put on the same outfit the next morning, bringing it into the realm of the everyday. Blazy suspected a more personal significance to the choice. “All my friends wear their boyfriends’ clothes,” he says. “I also wear my boyfriend’s clothes, when I’m in love, just because I want to be close, you know?” Her masculine borrowing has been remarked upon, but Blazy understood it as a reach for freedom of a specific kind.

“She didn’t want to look like a woman that men bought everything for. She liked to ride horses. She was always on the go,” he says. And her clothes were conceived by pragmatic circumstance. The Chanel beige came about because the jersey supplier Rodier had a discounted overstock in that color, which other clothiers hated. She lined her handbags with burgundy because she found it easiest to see her jewelry against that tone. Blazy’s Coco Chanel is less a visionary from nowhere than a woman who made thrilling clothes to answer highly personal needs: the specific constraints, freedoms, and passions that gave texture to her daily life, most of all with Boy Capel. “What you quickly find out is that Chanel could not exist, in the aesthetic we all know, if she was not in love with that man,” Blazy says.

The Chanel-as-love-story frame is his retort to those who would dismiss his everyday conceptualism as a poor fit for so lightsome a house. Yes, he’s designing from the play of ideas rather than from luxurious Lagerfeldian swoops of the pencil. But ideas, too, carry passion, sensuality, and even body memory; a tweed untransfigured by ideas of desire is just a tweed. (The Boy Capel romance may also serve as happy redirection, because Coco’s other famous love story, with Baron Hans Günther von Dincklage, linked her to Abwehr espionage.) “There’s an intimacy and sensuality in Matthieu’s work that Chanel also had,” Andrew Bolton says.

And understanding Coco as someone who designed by circumstance opened new realms for Blazy’s work. He puts a lot of stock in the house’s early affinities for what would now be called globalized culture. During the interregnum last year, one heard it posited that only a designer rooted in French life could catch the mood of so quintessentially Parisian a house. Blazy, a Parisian born and bred, recoiled from the claim. (“I disagree! I’m half Belgian!” he exclaims.) He cites André Malraux, France’s first cultural-affairs minister, who believed that local cultures are part of a larger global culture on which the whole world draws. From the house archivist Odile Prémel he learned that one of Coco’s earliest coats used a colorful pattern from Turkmenistan, rendered in monochrome. In the archive of Azzedine Alaïa (an obsessive Chanel collector), he studied a piece with a distinctive diagonal stripe that, for him, was like finding the fair-haired Tarim mummies in Xinjiang: proof of early cross-movement. “There are no references like that in the European world!” he says—but he recognized them from Persian rug making. The “Frenchness” of Chanel’s style was never strictly that.

GROUP HUG

From left: Models Dru Campbell, Aditsa Berzenia, Abeny Nhial, Fengjiao Long, Bhoomi, Zaya Guarani, Charlotte Boggia, Awar Odhiang, Luiza Perote, and Achol Ayor. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech. Photographed by Rafael Pavarotti. Vogue, December 2025.

Today the brand, like most big names in luxury, does a large share of its business in Asia and the Middle East. But it has remained unusually deliberate in not throwing itself to the winds of market opportunity. It has never had a men’s collection, a children’s collection. With the future often said to be about online commerce, it doubled down on boutiques. “Chanel is about staying super-focused—you cannot do everything and be the best,” Pavlovsky tells me. This might be true: Though Chanel has been experiencing the same luxury-market squeeze as all brands (a downturn Pavlovsky insists was expected after wild growth in the sector), its dip has been softer than most.

For Blazy, Chanel means, among other things, a distinctive approach to couture. “There is something about the Chanel lightness that I really want to explore,” he says. “Couture doesn’t need to be heavy. It doesn’t need to be big. It’s something about the making, how it falls on the body.” In the Belgian style, he likes to work in the round, with scissors in hand.

“The way it worked before was that Karl would design, the atelier would translate, and no one would touch the piece—it was immediately holy,” he says. “I might start with a suit, and by the end of the day it will become a dress. The first time I cut a piece—or a bag!—everyone was, well, not horrified, but surprised.”

He is standing in his studio now with Krzysztof J. Lukasik, an accessories designer, and Marie-Valentine Girbal, his research head, in practice his right hand. The two of them communicate wordlessly: When Blazy is uncertain of a decision, he will often glance at Girbal, who will tell him, with a flinch of the eyes, what she thinks. (“At some point, we just got in sync,” she explains.) Where Lagerfeld’s creative entourage comprised an inner circle of male models and soigné sophisticates, Blazy’s tribe of top deputies, brought from Bottega, tend to be easygoing millennial design geeks: If they weren’t huddled here, designing the collection for one of fashion’s largest global brands, one suspects, they might be in a basement office somewhere putting out a good small magazine. “It’s nice to be surrounded by those kind of people,” says Artur Davtyan, Blazy’s design director and his other longtime right hand. “You’re able to have conversations based not only on aesthetics—‘We like that’—but on trying to build concepts around collections.”

Now jazz is playing. Girbal and Lukasik are reviewing prototypes for bags. When Blazy started the collection, he envisaged allusions (he wasn’t sure why) to Le Petit Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s novella. So the team has been experimenting with globe-shaped “universe” bags, made of metal and painted with two layers of enamel, studded with stones as stars. They put him in mind of a planetarium he visited as a boy. He unclasps a prototype and peers inside.

“Wow!” He glances at Girbal. “Do you like it?”

“Yes,” she says.

“I’m going to have this one, if possible, in my office,” Blazy says, eyeing the orb thoughtfully.

A new group enters, to review swatches. A three-decade veteran sourcing expert of the Lagerfeld days suggests an evening bag in eggplant-colored tiny, shimmering sequins, a style that had great success at Chanel in the past. Blazy resists: He isn’t wild about that purple, and he can’t abide small sequins. “It’s personal trauma,” he says.

“Would you like to see maybe a storyboard of these bags we did over the past year?” she asks.

Blazy smiles. “I will tell you my trauma,” he says. One Halloween, he explains, while he was living in New York, working at Calvin Klein, he agreed to dress up in drag for the first time. His dress was covered in small sequins. Almost immediately, he got stuck in an elevator for two hours. He had to crawl out over the feet of firefighters. “Just to finish my walk of shame, I went out of the hotel and couldn’t get a taxi,” he says. He smiles and shakes his head: “No small sequins.”

Blazy likes to remove himself from the studio for a few minutes between sessions, to allow the space to be reset and to give his design colleagues a chance to prepare, confer, or kvetch without him present. He exiles himself to a balcony for a cigarette. It is at such moments that the loneliness of the top job is palpable. Outside, he suggests that his approach on the matter of the sequins was typical of his management style. “Everything has to be done very respectfully, because we’re discussing ideas and colors, and taste isn’t universal—there are certainly no mistakes,” he says. His droll story about being trapped in an elevator was emblematic: friendly but resolute. “I think I would have made a good diplomat,” he says.

Afew days after our dinner, I meet Blazy for a café crème at a corner of the Parc Montsouris, at the southern periphery of Paris. It is a glorious morning—bright, breezy, and fragrant. Tufts of acacia pollen drift down the slope of the rue d’Alésia, and the neighborhood is out for morning errands. This is a landscape of Blazy’s youth; he grew up not far away and visited one of his friends here while a child. As teenagers, they would crash parties at the nearby city university. “It’s really the place where I had my first feeling of freedom and fun,” he says. “It feels like Paris, but it’s not designed to resemble a postcard.”

As a lackluster young student, Blazy was sent to a Marist boarding school in the wooded southern region of Ardèche, then to a military school in Britain. At La Cambre, the Belgian design academy, he studied design alongside music and art, and, as a young employee at Raf Simons’s eponymous brand, he was taken around to galleries. To this day, he is a careful, discerning collector of art and fashion alike, but he has been most arrested lately, he says, by art that exists outside the market.

That afternoon, he will meet with Richard Peduzzi, an 82-year-old scenographer whom he plans to collaborate with. “Marie-Valentine sent me a podcast he went on,” Blazy explains. “I thought he was very subtle—I liked what he had to say. Sometimes you meet people and you connect immediately. The last time I had that with another creative not in my field was with Gaetano Pesce.”

In 2022, Blazy and Pesce, who died last year, collaborated on the set for a Bottega show that involved a special poured-resin floor. Blazy asked for someone to come to the studio to make a sample version. He entered to find a man named Stefano, Pesce’s right hand, pouring resin. “My heart stopped,” Blazy says—and not because of the floor. Still, Blazy, who was previously in a 17-year relationship with the designer Pieter Mulier, the creative director of Alaïa, felt unsure how to make a romantic approach. “It took quite some time,” he chuckles. “And some letters.” After months, they connected. Blazy, who did not speak Italian, learned it. “I’m in a good place now on the personal side—of course I have pressure, but I’m in love,” he says. “I’m keeping it very low-profile. I feel preserved.”

FLOW STATE

Awar Odhiang in a Blazy dress that hearkens back to the house’s early-20th-century origin story. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech. Photographed by Rafael Pavarotti. Vogue, December 2025.

He leads me up the exquisite rue du Square Montsouris, a climbing ramble of cobblestones sweeping past the front gates of narrow houses overhung with rose vines. We pause at the end to admire a white modernist apartment building designed by Le Corbusier.

“You have all these Art Nouveau or 1880s almost-countryside-bourgeois houses, and then at the end of the street, boom!, this Le Corbusier,” he marvels, then adds, “Maybe when I stop fashion, I can do tours.”

A few blocks away, a different narrow street, we pass another artifact of modernism, its broad façade catching the morning sun. Blazy gazes at it as he passes without stopping, then turns to admire it from afar.

“I just bought this house,” he says shyly.

It is his second major real-estate acquisition in Paris. While still working at Bottega, he bought the singular house near his childhood home long owned by the sculptor Valentine Schlegel—an artist, who had recently died, with whom he felt special affinity—and he is currently restoring it for use as a shared arts space. This house, though, will be different: It is a place intended for his personal use as a studio outside Chanel—a place he can work on the weekends, away from the pressure of the office. “It’s to allow myself to breathe,” he says. “Marie-Valentine can come to work there as well, and it’s a place I can receive people, because I don’t like to receive them at home—it’s too private.” (It is also a space he shares with his sister.) “With this kind of job,” he adds sheepishly, “you sometimes have to entertain people.”

We pass the house quickly; then he looks back. “It feels quite strange to know that I live here as well, in this house,” he says, and for a moment it is unclear whether he is referring to the building in front of us or to Chanel. He smiles. “That would have been a dream that I would never have allowed myself to have.”

Invitations to the October show arrive with a charm pendant shaped like a miniature house; peering through a tiny lens in the façade, one could make out the date and location of the show etched across the interior. It was a statement about looking closely, but also about emphasizing the quotidian intimacy that is a hallmark both of Blazy’s project and of the familial mood that drew him to Chanel.

“I thought it was quite beautiful that, in French, house and home is the same word: maison,” he says. “This house operates differently: It’s a family business. It’s run by people who have a feeling of togetherness. The doors stay open between one department and another. There is what we call a bienveillance—a kindness.” With this kind, quotidian, homey conception of the house, one felt, Chanel had ceased to be the old house of Karl Lagerfeld. It was now the house of Matthieu Blazy.

It is the day before the show, and Blazy sits at a small table at one end of a room in the Chanel offices. Flowers have been arriving, including an enormous bouquet from Raf Simons. Blazy has not slept much of late but has the glow of creative accomplishment: Over recent days the pieces, the looks, the show have locked into place. “I’m very happy,” he says. Music in an elegiac mood is playing: Ray Charles and Diana Krall singing “You Don’t Know Me.”

“At the moment, there are 77 looks prepared, which is maybe too much, but maybe also just right. Editing for whom—you know what I mean?” he says. “We are Chanel. It’s a show.”

A show, in Blazy’s view, is its own gesture. “It’s going to go quite in a lot of directions. I need to test ideas. I want to make mistakes. It doesn’t have to be perfect—it’s a first show. It’s a proposal.”

Since the summer, he has focused on the show’s major themes. “Gabrielle Chanel was the full paradox—she made herself the equal of the man, but at the same time, she was this séductrice at night.” He leads me to the looks. “The first part of the show is really about this paradox.”

A model enters in the dress that will finish the show—a skirt, worn with a simple white T-shirt and inlaid with colorful feathers and flowers made of woven raffia, which required hundreds of hours of handwork to create. “I wanted something very joyful, so it’s an explosion of flowers, almost like a Flemish painting. That’s what I see in it. My team sees a piña colada.” He grins.

Blazy never shows even his closest deputies the runway set before the day of the show, the better to keep it a completely fresh space. As guests stream into the Grand Palais on Monday night, they first look up. Suspended from the ceiling (and half-sunken into the ground) are 15 enormous planets: a young universe, an elemental sky, the famous backdrop of Le Petit Prince, a futuristic vision of the deep past. And Blazy’s childhood planetarium. Then they look down: The floor of the Grand Palais has been completely remade in a black resin dashed with sprays of color, like the galaxy forms of the known universe. The floor is smooth and reflective, so it catches the reflections of the planets. It is dashed, in patches, with sand, to give it a roughened quality, like a surface burned by time. And it goes on as if infinitely.

The surface was made by Stefano, Blazy’s boyfriend. Through the summer, they refined it together, testing colors and forms. It is not beside the point that the exquisite surface on which all of the show’s guests now walk—the platform on which the models would trace their runway paths—was made by hand and fashioned by two people in love.

TRUE TO FORM

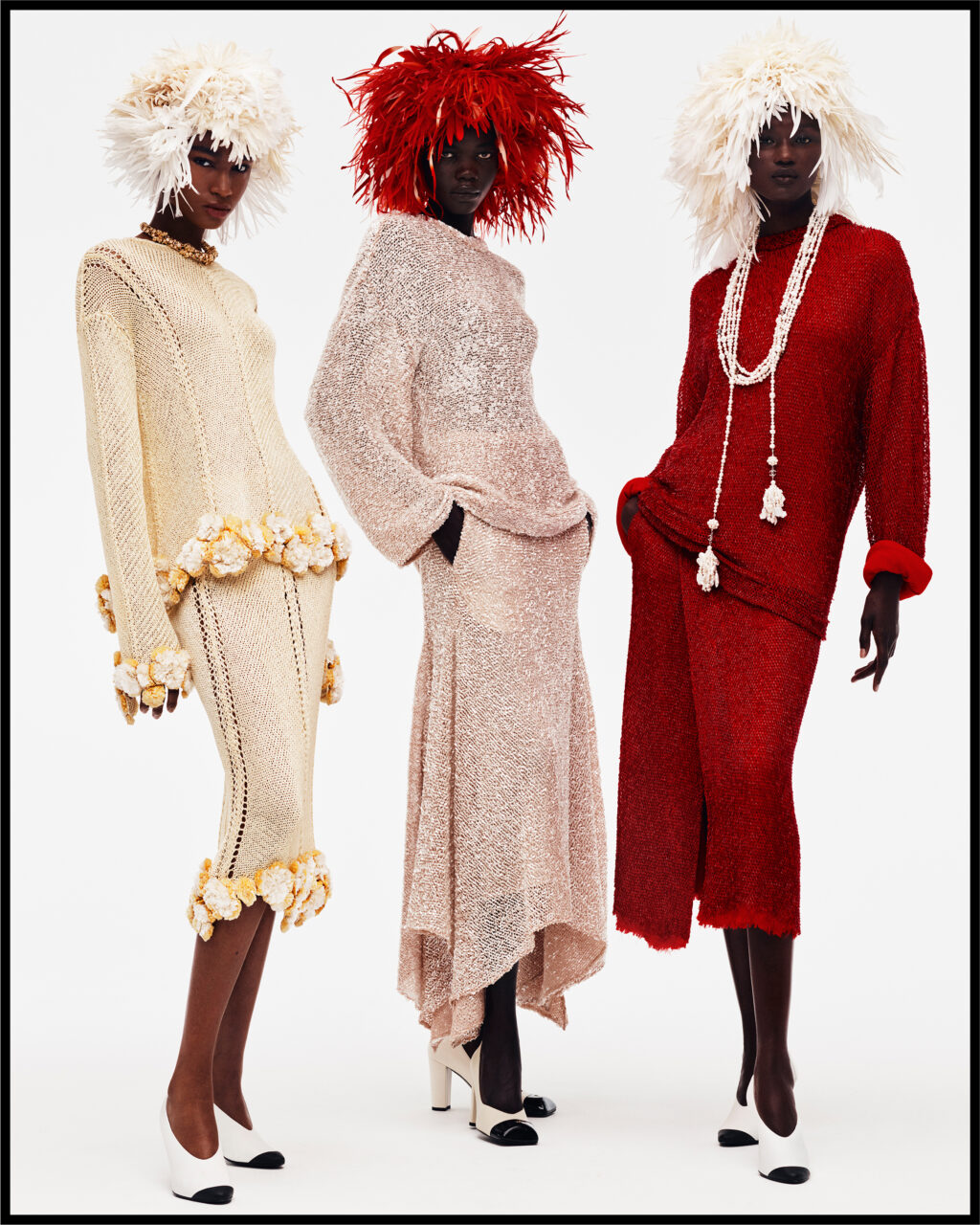

From left: Models Dru Campbell, Achol Ayor, and Abeny Nhial. Fashion Editor: Amanda Harlech. Photographed by Rafael Pavarotti. Vogue, December 2025.

At 7:59, a thunderous clap followed by the sound of harp glissandos sends everyone to their seats. A few minutes later, strings in Debussyan minor ninth chords wash in, interspersed passages from an eerie outer-space whistle.

The lights go down; the first look crosses the floor. Blazy has created a two-button Chanel jacket from the silhouette of a man’s gray coat, with pressed trousers—the version of the garment he cut on his first day in the studio. In her left hand, the model carries his take on the classic 2.55 bag, fitted with pliable metal within the sticking, so that they can be scrunched and bent into new, ragged forms. “They look like John Chamberlain. They look like car crashes. They’re lived-through-life bags,” Blazy told me. On the model’s ears are spiky white earrings—his interpretation of the Chanel camellia.

The third model wears a blouse of the burgundy color with which Coco Chanel lined her bags; the fourth has on a blouse and simple-looking wrap skirt entirely in silk—a look about freedom and motion, with the occasional flash of leg. “It is very interesting to have women who are covered, but when they move, they’re exposed—it’s very sensual,” Blazy says. But this paradoxical sensuality, he thinks, leaves women in control. Blazy divided his show into three chapters, and this first, called Le Paradoxe, brings power and seduction into conjunction. A red sequined two-piece flapper-esque dress appears. The sequins are small. (“I changed my mind,” Blazy says with a grin.) A model in an adaptation of Coco Chanel’s classic little black dress carries a clutch shaped like an egg. (“I love an egg because it’s the start of something.”)

Then all at once there is a men’s white shirt with an evening skirt—“the ultimate paradox,” in Blazy’s words. The shirt was made with Charvet fabric and technique; simple and elegant, a kind of proof of Coco Chanel’s love.

Blazy’s second chapter is called Le Jour—as in the everyday, the movement through ordinary life. “The silhouette is already starting to be more feminine,” he explains. “It’s closer to the body.” But he began innovating intensely with fabrics and construction. What looks at first to be a classic Chanel suit is actually a skirt hung directly from the hem of a sweater, like a dress; it sways and dances about the hips as the model walks. Blazy sends a few white dresses down the runway, quietly signifying, he says, his marriage to Chanel: “Something old, something new, something borrowed, something blue—I like that formula.”

Then come suits with men’s shirt collars and inspired by the patterns of menswear, rendered in dégradé to become flat, like a women’s dress: the two sides of the paradox merged in a single garment. Blazy exaggerated the frayed hems that Coco Chanel loved into ragged edges by letting the cloth be overtaken slowly with tiny hanging strings of beads. “It’s this aristocratic gesture that you don’t give a fuck anymore—you wear your clothes over and over because that’s how you feel comfortable,” he told me. “It’s not fringed, it’s used: cherished and loved.” The chapter also included Blazy’s “scarecrows”: fine cotton woven to resemble a potato sack, with strands of raffia in the blouse like wheat.

“Everybody who’s been paying attention knows that Coco Chanel came from a peasant’s life,” says the actor Pedro Pascal, who marveled at the scarecrow looks from the audience. Blazy explains, “Coco Chanel took the clothes of the worker—clothes that you could move in—and gave them to the aristocracy. It becomes the modern wardrobe. But that came from something functional—and poor.” In a hall filled with people who had emerged from black cars it was, to him, an insistence on the fashion power of the everyday.

The last chapter, L’Universel, is Blazy’s tribute to Chanel’s global roots and pluralistic present. The patterns are “zoomed-in” versions of tweed, which come to resemble patterns from across the world. The colors, which range from whites to grays and bold orange-reds, are direct from the Chanel archive. The music turns to French rap as the clothes, woven in silk, breeze through the air. There are suits. There are classic dresses embroidered with bright raffia flowers. There are transparent versions of the tweed, and what Blazy calls “bijoux ladies,” hung with layers of flapper jewels. Then comes the final look, the Belgian-flower-piña-colada dress, worn by the model Awar Odhiang. Applause breaks out long before she exits the stage. During the finale, she grins and takes a wild spin around the center of Blazy’s floor with her hands in the air. Nicole Kidman describes the mood of the collection to me as “true love.”

At last, the designer appears from a stairwell. The Grand Palais is on its feet and sending cheers. Blazy gives Odhiang a deep hug, jogs around the runway, and flees toward the exit, smiling. That night, he says, he will allow himself to walk the long way home.

For Annie Leibovitz portraits: hair, Duffy; makeup, Kana Nagashima. Produced by AL Studio. Set Design: Mary Howard.

For Rafael Pavarotti fashion photographs: hair, Karim Belghiran; makeup, Ammy Drammeh; manicurist, Dawn Sterling; tailor, Cléo Lacroix. Produced by Ragi Dholakia Productions.

Editor

Nathan Heller