Servers weaved between guests to offer delicate canapés, and champagne glasses clinked to sing joyous tunes…inside Hauser & Wirth’s new gallery space in Central, the crowd was abuzz with anticipation as contemporary artist Zhang Enli prepared to unveil “Faces”, his inaugural exhibition in Hong Kong.

Minutes before the show opened to the media, Zhang pushed open the tall glass doors of the gallery. Wearing his signature black beanie and red shirt for good luck (according to feng shui), he looked at both sides of the street before disappearing around the busy Queen’s Road Central corner for a smoke break.

They say that artists have their eureka moments during smoke breaks like these — and indeed, it is during Zhang’s brief respites from creation that he weaves together the titles of his paintings, all of which come after his pieces are complete.

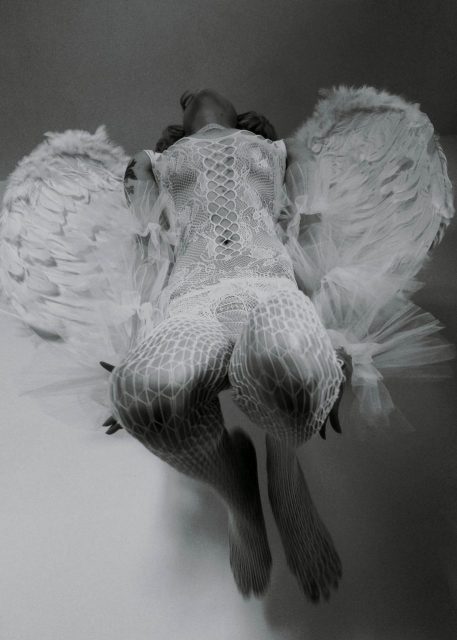

Zhang Enli, A Guest From Afar, 2023, oil on canvas, 200 x 400 cm

Photo: JJYPHOTO

On a monumental canvas, loose mediated traces float above thin layers of sangria, cyan and muted swashes of paint. Uneven lines swirl across the surface surrounded by loose strokes seemingly squiggled around. In Zhang Enli’s eyes, this painting captures “A Guest From Afar”.

People may think that Zhang is painting portraits of the world, but to the artist, everything in this world is a portrait in itself.

Spanning more than three decades, Zhang’s practice can be divided into four main periods: Emotionally charged figure paintings in the 1990s, nuanced still life of quotidian objects in the early 2000s, “space paintings” in the mid-2000s, and gestural portraits beginning in the early 2010s. Honing in on the use of colours, brushstrokes and their interplay, Zhang has arrived at his conceptual portrait style featuring loose and free brushwork.

To say that Zhang transitioned from figurative painting to abstract would be an oversimplification of his philosophy towards art because he believes that there is no clear distinction between the two genres. But, his arrival at this understanding didn’t come overnight.

When Zhang began painting as a young man in Shanghai three decades earlier, information dissemination was limited which meant that his understanding of the world was too. He didn’t study at an art academy nor graduate with a degree in art history. In the late 1980s, Zhang would spend months on a painting for a chance to be exhibited in group exhibitions, which occurred once a year or perhaps two.

In a conversation with art critic and curator Mr Li Xu, Zhang reveals that “all these things derived from a special way of thinking that was characterised to a special period of time. Later works are based on and develop from the works of the 1990s.”

View this post on Instagram

Back then, Zhang painted his immediate surroundings – those of ordinary people like butchers in “Two Jins of Beef” (1993), which is now part of Long Museum’s collection. Figures were depicted in full, from the fold in their clothes to the veins in their arms. Arresting colours leapt from the paintings charged with energy and loaded with rage.

Since this era of still-life, he has attempted to remove personal feelings from artworks and focus on deeper observations of the world around him. Large paintings examined specific objects in minute detail – how lines curved around the surface of different balls in “Big and Small Balls” (2012) and how bendy metal wires caged squished white volleyballs in “Balls” (2007). Later on, he would go further to narrow his focus to the movement of wires and the way they tangled together in different arresting formations.

Undoubtedly, these years of examining curves and lines helped him develop an acute sensibility towards the emotive traces indicative of his current style. There was just no telling then where it would all lead.

These days, he lets his subconscious take the reins. “Subconscious is a question,” Zhang peels back the layers of his mind, “Only with a question can you develop logic. This question propels you to do what’s on your mind.” How do we need to paint today? What do people need to see? What do people want to express? These are the questions that push him further.

Now, more than anything, Zhang’s works asks us to look within — to dive into the internal states being presented before us and feel all the emotions it evokes. Pushing the traditional boundaries of portraiture, Zhang captures the internal complexities of people’s minds in the paintings he exhibits. The correlation between the artworks and their titles are not immediately perceptible. In fact, when asked about the colour symbolism of his works in relation to the painting’s title, he said, “there is no relation” with no hesitation. “It’s a configuration of society…or all living things,” Zhang explains. Rather than consider these titles a guideline, let them be a springboard for your imagination to reflect on what you’ve observed about life. If ever you find yourself before one of Zhang’s conceptual portraits, consider it a mirror. As much as they might be about the people described in their facetious titles, they could just as much reflect a trace of you too.

Editor

Karrie LamCredit

Lead Image: JJYPHOTO