Legendary costumer Kate Hawley is no stranger to outfitting bombastic blockbusters. Over the past two decades, she’s worked on everything from Guillermo del Toro’s Pacific Rim to Suicide Squad, with a smattering of exquisite period pieces thrown in for good measure, too (notably, del Toro’s sumptuous Crimson Peak and The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, for which she was nominated for an Emmy). Now, she’s reunited with the beloved Mexican auteur for what is surely her most ambitious and jaw-droppingly stunning project to date: Frankenstein, an operatic retelling of Mary Shelley’s Gothic classic.

In it, Hawley achieves the impossible: she dresses Oscar Isaac’s reckless scientist Victor Frankenstein in drool-worthy velvet coats and eye-popping jewellery, and Mia Goth’s Elizabeth, the object of his affection, in some of the most extraordinary ensembles I’ve seen on screen this year – silk ballgowns painted with swirling planetary configurations; swooningly beautiful, brightly coloured veils; halo-like feathered headdresses; tulle-lined fans; rare archival Tiffany & Co jewels; and a ghostly, ethereal, many-layered wedding dress. Some of the looks made me gasp audibly – and yet, somehow, not a single one distracted me from the sweeping story of the visionary who plays God, and in doing so, brings about his own destruction. They only brought me deeper into del Toro’s magical world.

Come awards season, an Oscar nomination – Hawley’s first – seems inevitable, and a win would be incredibly well deserved, though she does, of course, face stiff competition from the likes of returning victor Paul Tazewell for Wicked: For Good, Sinners’s Ruth E Carter, Hamnet’s Malgosia Turzanska and Marty Supreme’s Miyako Bellizzi.

When I meet Hawley, in a grand suite at London’s Corinthia Hotel, the charming Kiwi – who, coincidentally, was first introduced to del Toro by The Lord of the Rings’ Peter Jackson, with whom she’d worked on The Lovely Bones and the Hobbit movies – is at the start of what will be a months-long promotional tour. Frankenstein is finally in cinemas, a new exhibition on the film, Frankenstein: Crafting a Tale Eternal has just opened at Selfridges, and the sumptuous epic is due to land on Netflix on 7 November.

Before then, the costume designer tells us about taking inspiration from beetles, the Biba-esque ’60s dreaminess of Goth’s Elizabeth, and why a ’70s Mick Jagger influenced the look of Isaac’s Victor.

You’ve collaborated with Guillermo many times before. What were your starting points this time?

Guillermo is an artist and a visionary in his own right. In his body of work, he’s heavily influenced by Hammer horror films, Mario Bava, all of those wonderful ’60s references, and that horror is full of colour, and very visceral. There’s common themes that run through Pan’s Labyrinth, The Devil’s Backbone and so on – and with every story, my observation is that he’s revisiting, reworking and reinventing those themes. So, I come to his films knowing a certain amount. I also come from an opera background, and we share a love of the operatic in all its forms. When we first met, Peter Jackson introduced us, and Guillermo didn’t look at my drawings or portfolio – he just looked at my bookshelf. I had Joel-Peter Witkin, Caravaggio, Goya. He said, “We can work together.” Having that shared language means everything.

Colour coding is really important to Guillermo, and I know he wanted the sequences in Victor’s childhood to be red, black and white. How does that colour story evolve as the film goes on?

The colour story does change. We have the world of ice and snow [in the film’s opening], which, to me, always felt like white, cream and blue, and we talked about white representing death. And for me, the captain is almost like St Peter at the gate. Guillermo is using all this biblical imagery. It was always about finding the right tone and thinking about how far we’d push these moments. In some instances, Guillermo was like, “Kate, much bigger, more!”

Victor’s mother in a bright red veil, in one of the scenes from our hero’s childhood, where the key colours are red, black and white

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

What was one of those moments?

The veils! That’s a bigger moment. And in other moments, you need to pull it back so the focus can be on something smaller, otherwise it’d take you out of the story. The colour palette is key to that. For instance, Harlander [Victor’s wealthy patron played by Christoph Waltz] has his colour palette. But then you have Elizabeth, and she keeps shifting. It’s like a metamorphosis. Her colours reflect each of the other characters. So, through Victor’s eyes, when he first sees her, she’s almost like an angel. Then we have Elizabeth echoing the red of Claire’s [Victor’s mother’s] coffin from the funeral scene. She’s almost fleeting, and becomes all these memories of all these women. She’s quite a stylised character – she’s the mother, she’s the Madonna. My job as a costume designer is to serve my director and the text. In this case, I had two texts – the script and the novel – and with both, it was emotional. We all bawled our eyes out. Guillermo tells me I cry all the time.

Christoph Waltz’s Harlander, in his distinct, more muted colour palette.

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

I cried so much watching this, I have to tell you.

Did you? [Beams] Oh good. Guillermo will be so happy. This story does that to you. There’s a desperate sense of loneliness in the cold, the skeletal trees, the air of melancholy, the way the creature is born with many body parts and memories [as a result of being pieced together from corpses]. It’s a very classical fever dream. With all of these references – the Caravaggios, the Caspar David Friedrichs – we wanted to evoke a sense of memory, melancholy, atmosphere and the idea that you could feel nature running through everything. That was hugely important for our textiles, too.

Elizabeth’s gowns have this almost extraterrestrial pattern. Where did that come from?

Guillermo writes little character stories, like bibles for each character, and there was always a whole thing about Elizabeth and her books. You see a little moment of that in the scene when they’re out dancing and she’s collected books at the market. Guillermo is very specific about what she reads, and one of these books was William Paley’s Natural Theology. And that, to me, imbued everything about the themes in the film – of religion and the wonders of nature. If you look at the ends of Victorian books, there’s incredible marbling. Guillermo also wanted to talk about her love of insects and cells. And in Victor’s world, you almost feel like you’re going into the creature and seeing its blood cells. I wanted to suggest all of that through the clothing. We used malachite in some instances, too – we had real bits of malachite in the workroom – and my team also spent hours drawing up cells that we then got woven into fabrics, and played with the sense of scale. We even had a whole collection of beetles in our studio to take inspiration from. It sounds dodgy, but it wasn’t.

Felix Kammerer’s William, Victor’s younger brother, with Mia Goth’s Elizabeth, his wife-to-be, in her malachite-inspired silk ballgown

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

Very early on, we’d assumed this Frankenstein would be set in the 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment or Mary Shelley’s period. But then, Guillermo came back and went, “I’m setting it in the Crimean War.” So, you think, “How do we move away from the Dickensian interpretation of that period?” We didn’t want a brown world. We wanted it to feel modern, but still have a Gothic quality, and that’s where the colour came in.

Her jewel tones seem connected to this love of insects and the natural world, and often that’s seen in the jewellery, too.

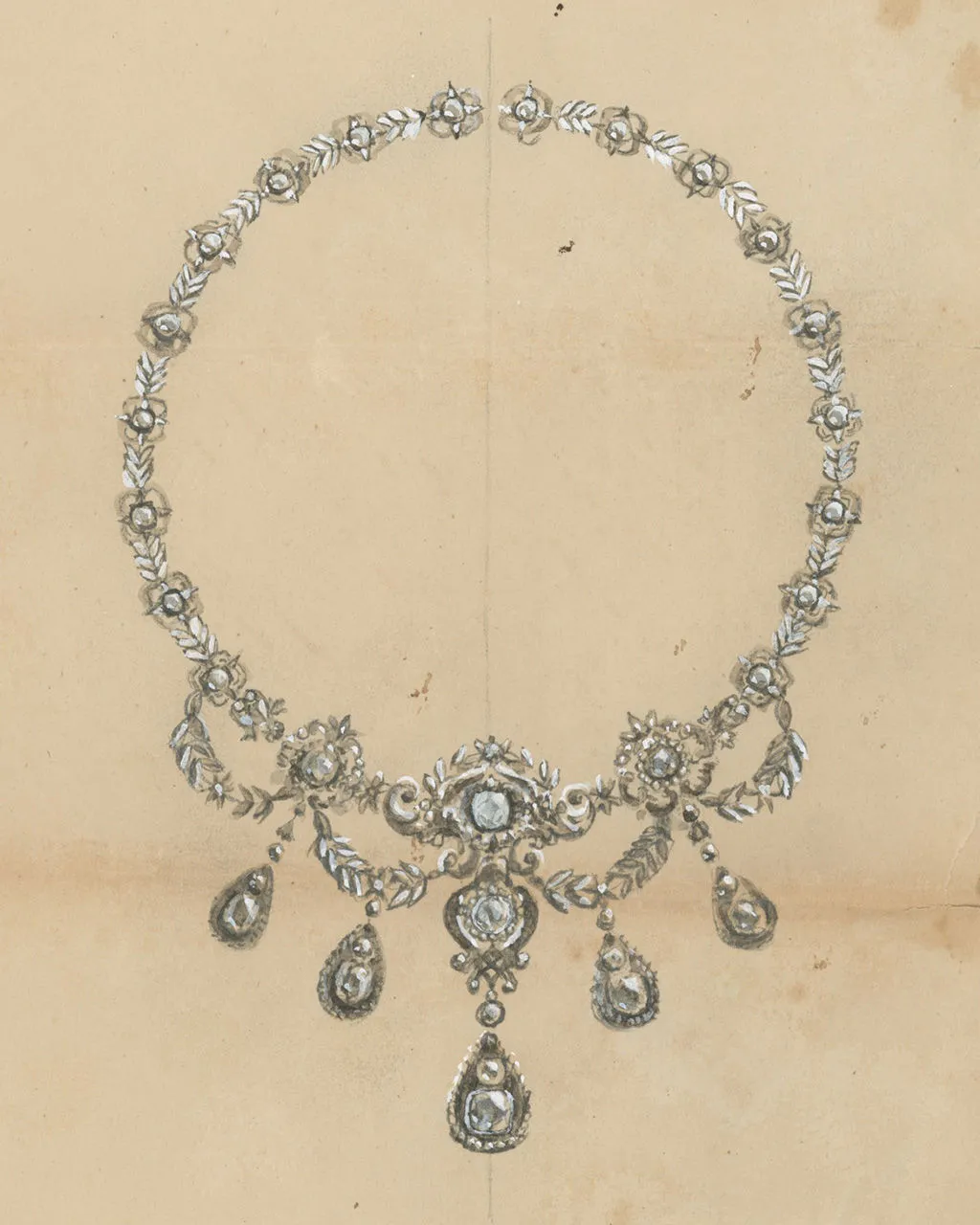

Absolutely. We partnered with Tiffany on the jewellery and I went to their archives. In their collection from over the last 200 years, there are echos to Mary Shelley’s world and the Age of Enlightenment, and then you have the Victorian period – in the 1850s, Tiffany were creating surgical instruments for the Civil War, and it was an age of modernism. So, you have the old world styles of Charles Lewis Tiffany, and then his son, Louis Comfort Tiffany, who comes in and rewrites the rulebook with much less traditional and more artistic, glass styles. The blue beetle necklace Elizabeth wears is a unique Louis Comfort Tiffany piece from the early 1900s.

Goth’s Elizabeth in her floaty blue ballgown, with her halo of feathers and the Tiffany & Co beetle necklace

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

That jewellery also influenced how we used colour, because it was all about tone and light and how the colours changed as you looked at them. In our dye department, we didn’t use black – we used purples, greens and blues, and layered colours upon colours to create those darker, deeper, richer tones.

Some of the necklines of Elizabeth’s dresses also seem to echo the most famous portraits of Mary Shelley herself?

Yes, definitely. We then kept her silhouette simple, but when it came to her crinoline fittings, Guillermo was like, “I want the really big ones!” That’s great for some scenes, but a bit of a nightmare in others. It had a knock-on effect on the art department because the doorways had to be made bigger to accommodate the crinolines! I was worried some of that might dominate Mia, but it doesn’t. She’s so extraordinary and luminous.

Mia saw Elizabeth as a woman of freedom, someone who’d run across the moors, in a way that’s maybe more Wuthering Heights. But she also has a different kind of strength. Seeing the creature, for her, is almost like a religious epiphany – he’s the embodiment of the natural world. So, there are shots which echo images of the Madonna and Christ.

Something else we talked about was that Elizabeth always feels like she’s disappearing. You can’t quite catch her – she’s the muse, and Victor’s chasing her.

I felt that a lot in the transparency of her fabrics and sleeves – there’s something quite ephemeral about it?

Totally, and we used veils, too. Veils are always contentious, because you see less of an actor’s face, but we used fabrics which still allow us to see them, and Mia went with that. We had them in strong colours, and they felt very painterly.

Some of her headpieces also look like halos?

The feathered ones and the bonnets really do. There’s a yellow bonnet which I basically copied from a painting of the Madonna. There are a lot of circles in the architecture of this film, and you’ll see that kind of religious, classical and mythological imagery echoed in [production designer] Tamara [Deverell’s] work too, for instance with the Medusa in Victor’s lab. Working with Guillermo is wonderful because every single idea ripples through every department. At one point, Tamara was running around adding green lichen around the tower set, to reflect the intense green of Mia’s dress.

And then when I was working with [cinematographer] Dan [Laustsen], he and Guillermo wanted to work with candlelight and single source lighting. It’s fantastic but actually quite hard. We did so many camera tests. We’d been asked to create all these saturated colours, but then the candlelight kind of killed them. For instance, with the first blue dress Mia wears, for weeks we had our heads in our hands, like, “How’re we going to do this?” A really saturated blue silk wouldn’t read, so we used layers and there’s actually lots of greys in that gown. You look through the lens, and it works.

Oscar Isaac’s Victor Frankenstein, in his plush red velvet coat which gleams in the candlelight

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

The wedding dress is exquisite, too. How did you construct that look?

That was the first look we created – once I’d done the Jesus-like bandages for the creature. The bridal look was really important, and this is Guillermo’s bride, not a Victorian bride. It needed to be period but also have the more modern sensibility that he wanted. It echoes the creature’s bandages and his skeleton framework. We built the dress like we built the creature, from the inside out – it has five layers of organza and a Swiss ribbon bodice, and we put that on the outside instead of the inside because, at this point in the story, Elizabeth is reflecting the creature more than she is Victor. The ribbons on her arms are also a lovely homage to [the 1931] Frankenstein and [the 1935] Bride of Frankenstein.

The dress is influenced by Swiss-German regional dress, and you can see the Frankenstein family crest, but one of my favourite things about it is how it moves. We used the lightest silk we could, and Mia’s constantly running in and out and up and down stairs, so it looks incredible. There’s also a slightly Biba-esque, sort of ’60s dreaminess to the look which comes through in the exquisite make-up by [make-up designer] Jordan [Samuel] and that very long hair by [hair designer] Cliona [Furey].

And the other important character in the film, from a fashion perspective, is Victor himself.

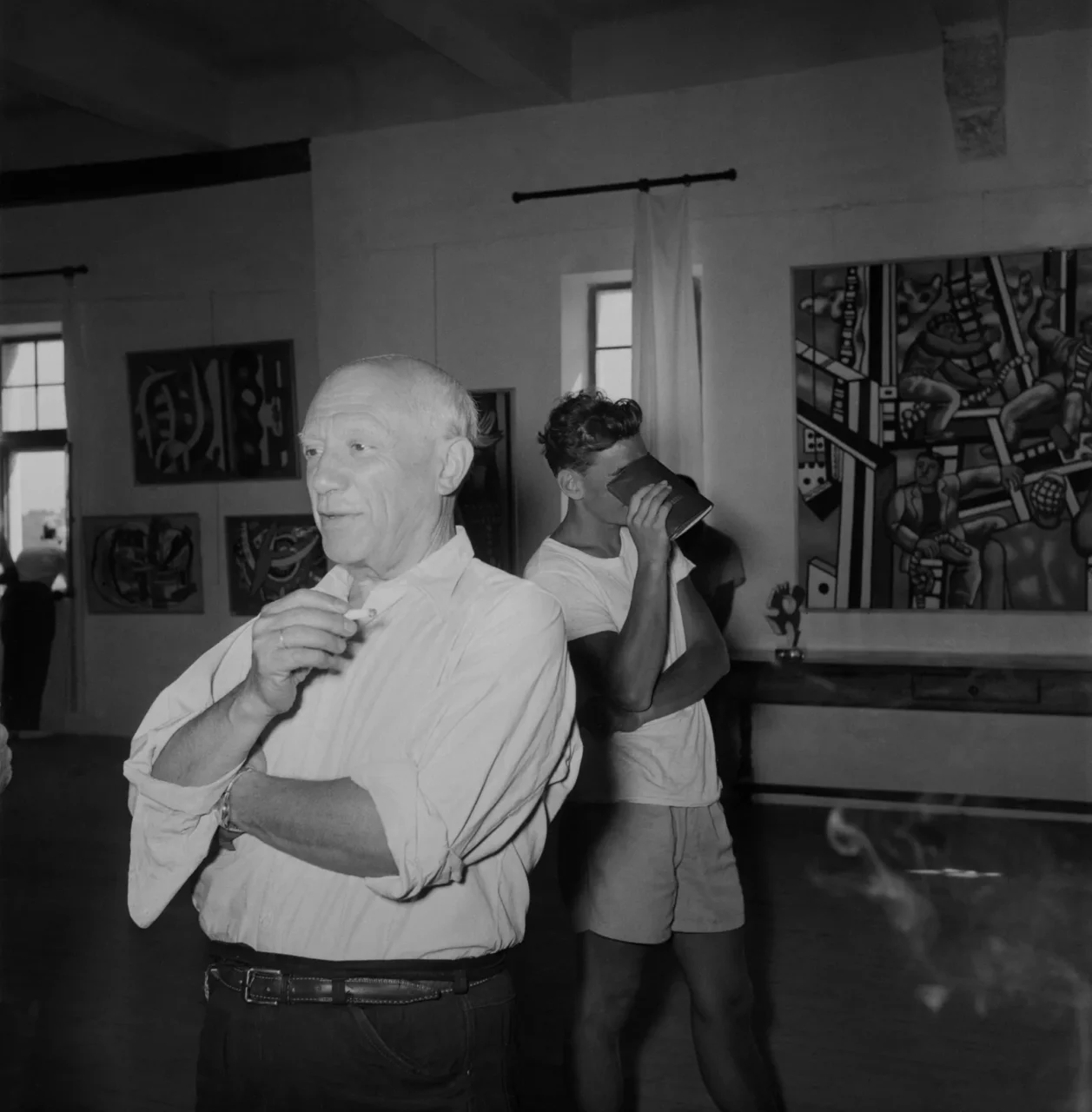

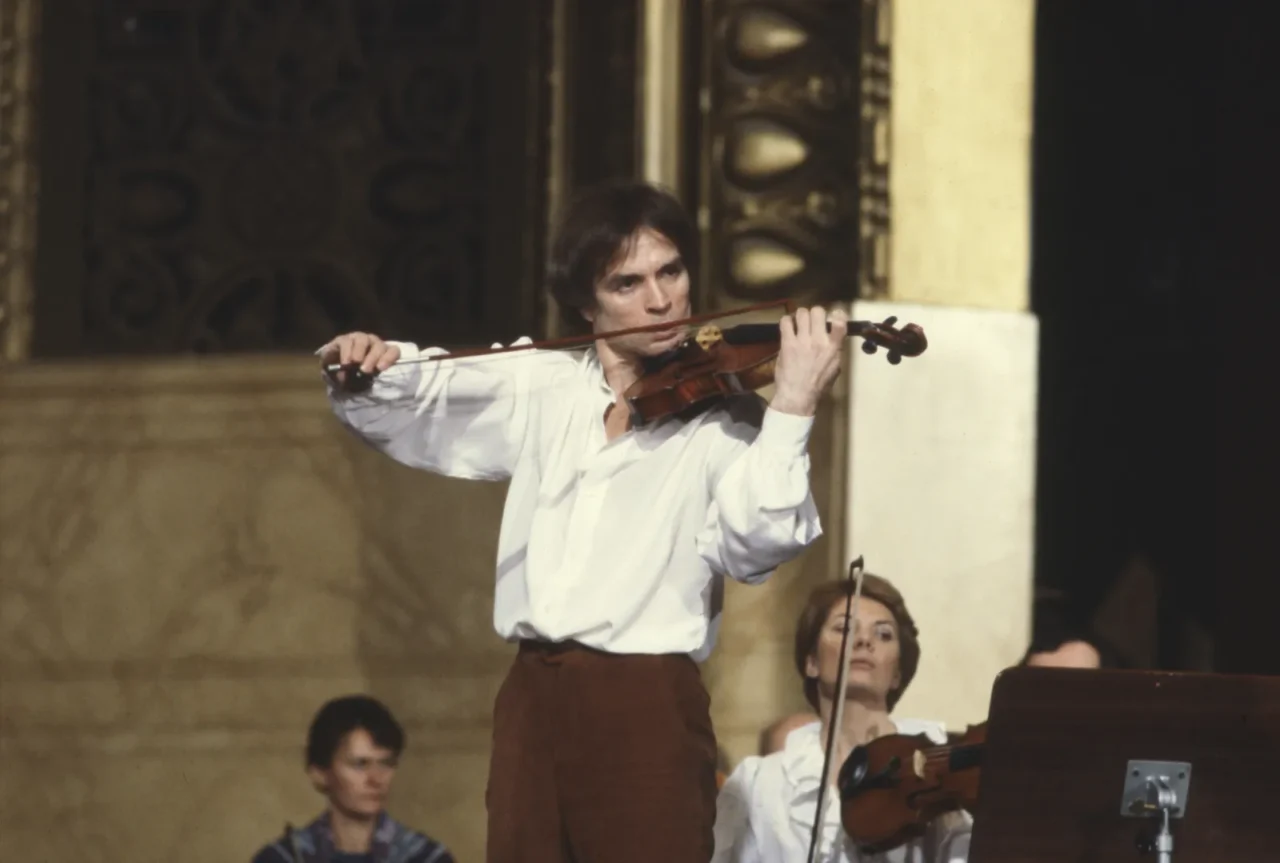

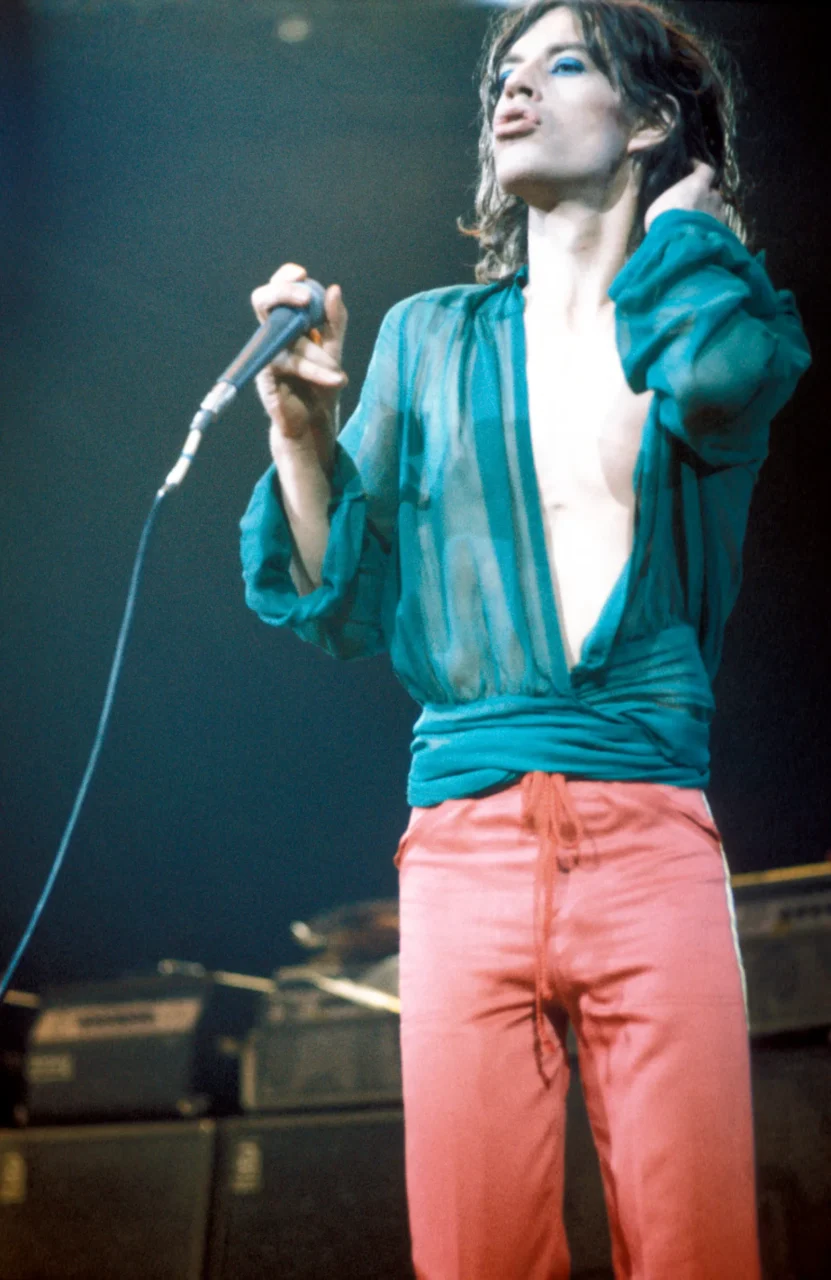

Our references for him included Mick Jagger in Soho in the ’70s and Rudolf Nureyev – we kind of wanted him to feel like a rock star walking on stage when he entered the lab. He’s a punk and a dandy. He comes from an aristocratic background, had no money but then comes into money, and wears his clothes with a real irreverence. It’s like Francis Bacon or Picasso – he wears his clothes to stay up all night and work. He plays with all this blood and viscera, and gets it all on his clothes.

Isaac’s Victor in his blood-stained shirt, worn with his trademark insouciance

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

One of my favourite garments in the whole film is his dressing gown. Oscar looks so beautiful in it. Victor wouldn’t go around just looking haggard – he has this William Blake energy.

Isaac’s Victor in his forest-green dressing gown, casually pulled over his bare torso

Photo: Ken Woroner/Netflix

Editor

Karrie Lam